Most emergencies are weathered by shelter-in-place, meaning we aren’t going to leave the home to go somewhere else. The home is the shelter of choice for them. ALL preparedness plans should begin with a thorough planning regiment and only then move to developing some type of emergency bag for evacuation. When we finally do get around to making these bags, they should support the PLAN we’ve already made.

There is one exception: the Get Home Bag.

The Get Home Bag (GHB) has a single purpose. To have the tools and resources on hand to get home from wherever you may be. The GHB should assume the worst case for getting home, such as in a blizzard, and having to travel on foot.

Here are some common assumptions:

- Inclement weather (dangerous cold, snow).

- Late start time (the emergency happened in late afternoon or early evening).

- Longest commute distance regularly encountered by the individual.

- Vehicle unavailable early (the vehicle broke down or was blocked initially or early in the trip, most of the trip will be walked).

- Reasonable physical condition. Able bodied, and generally able to hike for 8 hours a day with breaks with a 20 pound load.

In modern suburban America, the average commute is 16.2 miles one way. Extreme commute distances (more than 30 miles one way) is the fastest growing commute segment. It is important to be honest with one’s commute distance and train/prepare for it plus up to 50% more (detours, escape/avoidance, etc).

The first step is determining what the requirements for the GHB are. This article will assume a 25 mile commute one way, and that worst case, the GHB must be employed immediately (the trip is starting out on foot rather than abandoning the vehicle after several miles into the commute).

There is a check list at the bottom of the article. We’re going to ‘game’ this scenario a bit, to understand some of the intricacies. It’s better to read everything and understand the rationale for some items and determine if there is need for them in YOUR plan and YOUR kit.

Assess the situation

Overcome normalcy bias. Now. You’ve entered a situation that may require outside-the-norm decision making. Yes, when you leave work for the day and drive home, that work laptop is important. If you have to ditch the vehicle to walk home, is the laptop worth taking, or is it dead weight? It is important to become brutally honest about the situation, the priorities, and the consequences of decisions.

Hint: The password protected and encrypted laptop will be just fine remaining in the locked vehicle until you retrieve it. (It may not be, but seriously, get over it.)

How bad is the weather? Can it be reasonably navigated (such as 4 inches of snow or less)? How late is it? Is it imperative to get home as soon as possible? Is it possible to shelter at work/location until the next day? Most parents are going to think “I need to get home now!” to ensure their family is safe. Overcome this anxiety and collectedly assess.

Communications is important. Gather information via phone calls or radio. Have important numbers, emails, contacts in your phone. Have the very important ones hardcopied in your GHB notebook. It’d even better to understand HAM radio, repeaters, and have those you’re trying to reach equally versed. Some threat events will not allow communications. What is your school’s policy on holding kids until parents come? Do you and your spouse have a plan to enact in the case of no-vehicle no-communications? What is expected of each of you?

Hint: Texts will often go through a cellular system even though voice calls cannot.

Fully understand the situation as it pertains to you.

In the vehicle

A vehicle has ample space to store needed equipment and supplies and costs little resources to move it about. There are several things that can be put in the vehicle as options, and chosen for inclusion in the human-portable GHB to be used (we are assuming we will have to abandon the vehicle).

Common in-vehicle gear includes:

- Weather appropriate clothing.

- Emergency blankets.

- Emergency food, water.

- Tools.

- Maps/Atlas.

- Communications (CB, HAM).

- Electronics charging.

Of these, only a few items will be helpful during a worst-case Get Home effort. The maps, probably. Weather appropriate clothing, as long as it is suitable for hiking/mobility. “Stadium warmth” bulky clothing may be ill-suited for high exertion and mobility (but will be desirable for sheltering). Some food, some water. Useful tools may be limited to a saw, small hatchet, and pry bar. Bottom line, though, is all the stuff in the vehicle that could help the situation isn’t necessarily human-portable. Trying to drag it may not be helpful.

Primary activity: Walking

In a Get-Home situation, the primary activity will be walking. Yes, luck may provide a ride, or the vehicle is accessible, but we must plan on this 25 mile walk. What is needed for a walk of this magnitude?

First, we must be in reasonable shape. That means training. Recreational backpacking and hiking is the ultimate answer here. Proficiency with this activity will turn a get-home event into nothing more than a hike with more urgency than usual.

Hint: much of the gear obtained to enjoy this hobby will be directly usable in a get-home bag.

A practiced hiker/backpacker carries a 30 pound load for 8-10 hours a day on unimproved trails, averaging about 3 miles per hour on mostly level terrain. In those 8-10 hours are approximately 15 minute breaks per hour, a lunch taking about an hour, and generally one morning and afternoon extended “packs off” break of 30 minutes. Assuming a full 10 hour day, this equates to 3 hours of break, giving a total range of 7 hrs x 3 mph = 21 miles.

Some of the discontinuities in this data and the Get-Homer are that he may not be a ‘practiced hiker’. The stamina and surefootedness are earned. Another discontinuity is the 30 pounds of gear are recreation-intent, light weight equipment designed to support a pleasurable hobby. Much of it translates (such as a sleeping bag), but some does not. The Get-Homer may need protective weapons, tools to secure supplies (such as pry bars, etc), communications, and more. Water sources may not be as well understood as a researched and planned hike, resulting in more carrying.

Planning and training are critical to helping ensure a successful get-home excursion.

Pro tip: Store your phone and all spare batteries near your body while walking. The cold will greatly reduce battery life. Your body heat will prolong it. Keep conversations short. Possibly keep the phone off and only power on once an hour to send updates.

Secondary Activity: Shelter

Outdoorsmen spend a significant amount of time balancing clothing’s ability to retain heat during sedentary times and shedding heat during mobile times (assuming winter). High quality outdoor gear is made for this. Sweat is enemy number one. Gear selected must be versatile enough to accomplish these things. Modern military wear, prosumer-grade outdoor gear, and high-end hunting gear is designed explicitly for this. It must be researched, it must be tested. Shelter is survival priority number 1. Understanding the clothing in one’s gear must also be.

One of the assumptions was that the ‘event’ causing a Get-Home excursion to be necessary happened later in the day. In northern USA in December winter it gets dark at 5 PM. Worst case is setting out later than this, but much later and there should be a very compelling reason to set out and not wait until morning.

It is unlikely the average person will be able to hike through the night. Training and equipment may allow it, but after 4-5 hours the urge to bed down somewhere will be evident. Finding shelter is an art unto itself, as is making expedient shelters from natural resources. Abandoned vehicles, utility buildings, retail outlets, and more can serve as a means of getting out of the elements. The goal is simple: Get out of the elements, and find a way to retain warmth.

The expectation of getting a good sleep should be removed. It will be a shivering, cold, poor sleep filled with anxiety. It may even only be for a few hours before the weariness fades and the urge to get home overtakes it. All this should be expected. To help ensure the possibility of a regenerative sleep, we should be versed in fire making, have at least a very warm wool blanket, and a means of getting out of the elements. A good silicon impregnated nylon tarp is an excellent light-weight means of providing shelter. Whether in an ‘A-frame’ configuration or even as a lean-to setup to help retain some fire warmth, the wind/snow block is important.

The wool blanket may seem like a heavy, archaic form of sleep system, but it has multiple advantages over a sleeping bag. First, it is easy to get out from under in the event of a threat or other quick-reaction event. A sleeping bag can become a warm coffin in such a situation. Secondly, it retains some warmth retention even when wet, as the fibers are naturally hydrophobic. Thirdly, while wool may singe due to embers from the fire, it does not destructively melt like nylon will. Fourth, it can act as a cover or wrapping and still allow the user to be mobile.

Pro-tip: A mylar blanket does little to keep one actually warm. In a lean-to setup with a tarp, use the emergency blanket inside the nylon tarp to help protect it from embers as well as reflect a substantial amount of the fire’s heat back towards you.

Supporting equipment and activities

There are a number of training items, equipment, and necessities to support a get home excursion of this magnitude and under worst cases. The following items are a short list with some explanations.

Handgun and ammunition: Desperate times bring out the worst in some people and the best in others. It is despicable to prey upon someone in times of need. Protection is a foundation of all preparedness, and the fact that you’ve prepared does not create an obligation to help those that have not, no matter how desperately they demand or beg. The handgun keeps your life yours, and your things yours, unless you choose to do otherwise. Without it, the choice will be made for you by evildoers. Training required for effectiveness.

First aid kit: Moving out of one’s normal actions and environments brings inherent risk due to unfamiliarity. Risk potentially leads to injury. An adequate firs aid kit is essential, as is the training to use its contents.

Layered clothing: Everyone in the USA understands the idea of layering. No need to write more here.

Fire starting: Bic lighters, ferro rod, some dryer lint, and a half hour searching for suitable fuel gets you a fire. Know how to start one, know how to keep it going. Training required for effectiveness.

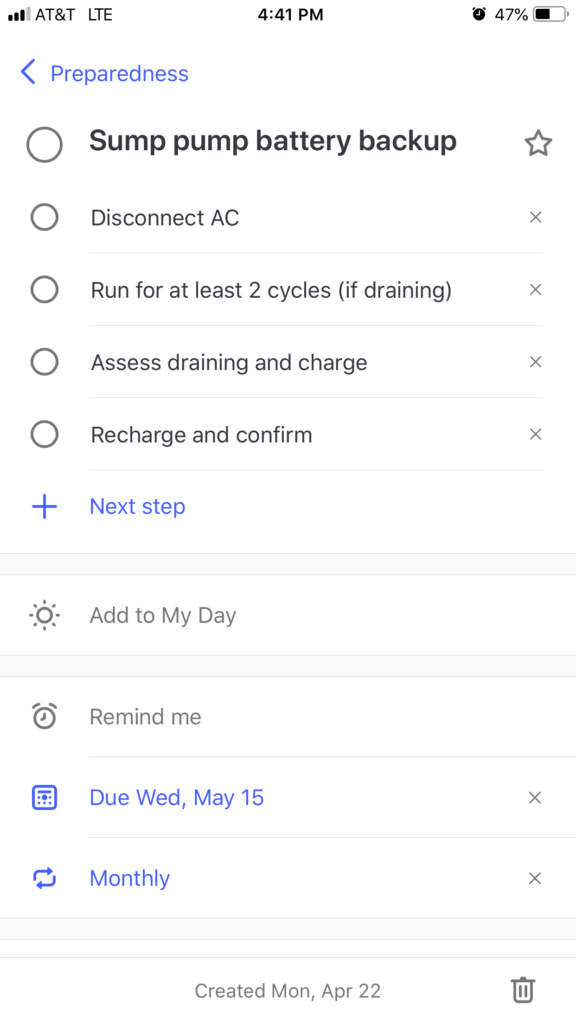

Hydration: K&B recommends a 40 oz widemouth Klean Kanteen with single wall construction. When moving, odds are water will not freeze unless it is exceptionally cold. The steel container can be used to boil water, or at least warm it up well for added comfort. Water filters are useless in the cold (the element will break from freezing). Melting snow is generally safe, but time consuming. Aquamira tablets can be used to purify water, but extend the reaction time recommended if the water is too cold. The average person will need 40-80 fl oz for a trip of this magnitude, and will be slightly dehydrated at its conclusion. Plan on 120-160 fl oz for this trip if possible.

Nutrition: A trip of this magnitude is able to be accomplished without food, but the body will be expending up to 4000 calories each day. No food will make it colder and more difficult. Some food, such as a high calorie emergency ration, or freeze dry meal, will be very beneficial.

Illumination: There are 3 categories of illumination: low level but long duration, medium, and high illumination with short duration. It’s important to have all three in one’s kit. Glow sticks are excellent for 4-6 hours (in the cold) where low illumination is all that’s needed. A headlamp can provide medium illumination (most have multiple settings now for low light and bright light, trading off duration). High intensity tactical flashlights are essential when defensive measures are required.

Cash: For a Get-Home situation, silver and gold will be utterly useless. Yes, survivalists of old, they will. A get-home situation is most likely at the onset of a threat event, and society as a whole will not have acclimated to a precious metal monetary paradigm. It would take weeks and possibly months for that. Cash on hand buys you options. Maybe some skis at the store, maybe a ride on a truck that was unaffected by the event, maybe a night in a hotel somewhere. Cash is versatility to obtain lacking resources.

Battery backups: Have spare batteries for all electronics. Spare batteries should be stored on one’s person to prevent power loss. For maximum resiliency use lithium ion batteries and buy gear that is compatible with Li-ion.

10 Essentials: Outdoorsmen have long understood the necessity of the 10 essentials. In their quest to pare down weight for more enjoyable hiking, they often remove things not used or seldom used from their packs. The exceptions are the 10 essentials, which stay a part of the pack regardless of frequency of use.

- First-aid kit.

- Knife.

- Sunglasses and sunscreen.

- Extra clothing.

- Rain gear.

- Firestarter and matches.

- Extra water.

- Extra food.

- Headlamp or flashlight.

- Map and compass

Some of these are covered elsewhere. The utility of the rest of these items should be self-evident.

Navigation: Using GPS apps, maps, and compass should all be a well-practiced skill set. GPS and map datums should match. Maps should NEVER show destinations! Plot courses to the nearest major intersection or significant landmark that you know how to get home from. Label each route home. Ensure your spouse has copies of these routes in case they have a working vehicle and can safely rendezvous with you (assuming you have communications). Likewise, have copies of their routes. Annotate with water sources, caches, shelter options, and other resources. Maps should be durable.

Everyday Carry on-body (Tier 1) and Get Home Bag (Tier 2) Checklist:

|

Tier 1 |

Tier 2 |

| Protection |

|

|

| Handgun |

Yes |

N/A |

| Spare mag |

1-2 mag |

2 mag |

| Holster |

Yes |

N/A |

| Melee handheld |

Tactical pen

Tactical flashlight |

N/A |

| Long Gun |

N/A |

N/A |

| Scabbard/sling |

N/A |

N/A |

| Spare Mag |

N/A |

N/A |

| First aid |

|

|

| First aid kit |

Pocket Kit |

First Aid Kit |

| Medications |

in Pocket kit |

N/A |

| Shelter |

|

|

| Daily clothing |

Yes |

N/A |

| Headwear |

N/A |

Wool hat

Full brim hat |

| Face covering |

N/A |

Shemegh/ bandana

Filter/Respirator |

| Spare Underwear |

N/A |

Yes |

| Base layers |

N/A |

1 Merino Wool |

| Midlayers |

N/A |

N/A |

| Heavy layers |

N/A |

Yes |

| Shells |

N/A |

Yes |

| Gloves (not work gloves) |

N/A |

1 pr glove liner

1 pr heavy |

| Socks |

N/A |

1 pr midweight wool

1 pr heavy weight wool

1 pr sock liner |

| Footwear |

N/A |

Hiking / Winter |

| Fire starting |

N/A |

Bic Lighter x2

Ferro Rod

Tea candles x2 |

| Fire perpetuation |

N/A |

N/A |

| Fuel |

N/A |

N/A |

| Shelter (expedient) |

N/A |

N/A |

| Shelter (normal) |

N/A |

SilNylon tarp |

| Insulation/Bedding |

N/A |

Silk bag liner

Mylar blanketWool blanket 1-2 |

| Hydration |

|

|

| Water |

N/A |

40 fl oz |

| Purification |

N/A |

Aquamira

Floss / Carbon / Bottle |

| Container |

N/A |

Klean Kanteen

bladder |

| Nutrition |

|

|

| Foods |

N/A |

Yes (2 servings) |

| Preparation items |

N/A |

N/A |

| Serving items |

N/A |

N/A |

| Hygiene/Personal |

|

|

| Nail clippers |

N/A |

Yes |

| Toothbrush/paste/floss |

N/A |

(optional) |

| Soap |

N/A |

Yes |

| Towel |

N/A |

Yes |

| Disposable wipes / TP |

N/A |

Yes |

| Hand sanitizer |

N/A |

Yes |

| Deodorant |

N/A |

N/A |

| Spare Glasses |

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

|

| Rescue / Mitigation |

|

|

| Knife |

Folding |

Full tang

Spare folding |

| Multi-tool |

N/A |

Yes |

| Pry bar |

N/A |

Yes |

| Saw |

N/A |

(folding optional) |

| Tape/Fastening |

N/A |

20′ duct tape

10 large zip ties |

| Hatchet |

N/A |

(optional) |

| Safety glasses |

N/A |

Yes |

| Work gloves |

N/A |

Yes |

| Needle/thread |

N/A |

Yes |

| Compass |

N/A |

Yes |

| Maps |

N/A |

Work to Home |

| GPS app / handheld |

smartphone |

N/A |

| Pace counters |

N/A |

Yes |

| TX/RX Radio + charger |

N/A |

Yes |

| Cell phone charger |

N/A |

Charging block

USB cord |

| Signal mirror |

N/A |

Yes |

| Emergency whistle |

N/A |

Yes |

| Flashlight |

Surefire E2D |

N/A |

| Headlamp |

N/A |

Yes |

| Glowstick |

N/A |

x2 red

x2 green |

| Ziplock bags |

N/A |

4 |

| Garbage bags |

N/A |

2 |

| Paracord |

N/A |

100’ |

| Emergency currency |

$100 in $20’s |

$100 in $5’s

$100 in $20’s |

| USB Drive + documents |

N/A |

Yes |

| Spare batteries |

N/A |

Battery block for phone

Tac Light: 1 refill

Headlamp: 1 refillOptics: 1 refill |

| Notepad |

N/A |

Yes |

| Pack |

N/A |

approx 2000 ci |

NOTES ON USING THIS CHECKLIST:

- Items marked N/A may not appear on that tier (for instance, you’re not expected to have 4 glow sticks on-body carry) but may be applicable for another tier. Items that have N/A for both tiers shown might be a bug-out-bag (tier 3), or bug-out-vehicle (tier 4) item.

- Some items have hyperlinks with suggested product.