One aspect of emergency preparedness is knowing when to vacate the home (bug out) and regroup at a safer location. To do so, many preparedness enthusiasts choose to create a purpose-made bug out vehicle to enable this relocation.

We here at Keep and Bear, LLC prefer to keep things realistic. That means unless fantasy vehicles are your hobby, odds are you’re not going to mod an old Deuce and a Half or store a Damnation Alley Landmaster in your back yard anticipating radioactive armored cockroaches.

The more measured approach is to select a vehicle that will serve in an emergency evacuation scenario, and will hopefully fit in with all your other daily needs. This can be difficult in some circumstances, such as needing a highly efficient vehicle for a long commute, that would fare poorly if roads became cluttered with debris.

Below are some considerations when selecting your next vehicle to have some BOV capability. The headings are not in ‘weighted’ order of importance.

Power

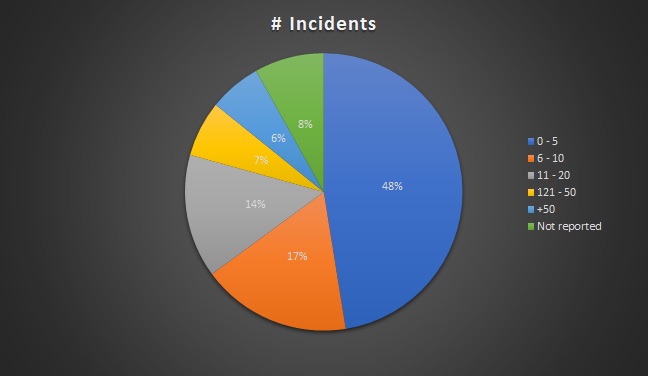

During the 2016 Fort McMurray Wildfire which enveloped nearly 1.5 million acres of land, many Canadians were forced to flee in vehicle. There are hours of harrowing Youtube footage showing a relatively orderly evacuation process. As seen in the video, vehicles were perilously close to the blaze. Certainly there were those who evacuated earlier, and those who came later at even greater danger.

One person who was interviewed regarding vehicles for this made the claim “larger pick up trucks with the ability to push stalled vehicles out of the way were more successful in escaping the situation”.

Independent of the nature of the emergency, stalled vehicles will be a problem. There will be those who didn’t gas up, or were at the low end of their fill cycle when the emergency hit. There will be people attempting to escape in vehicles that are not mechanically sound, but it’s all they have. These vehicles become problems for everyone behind them, and having a vehicle that can push things out of the way is a BOV must-have.

Terrain capability

The most frequent emergency travel conditions are weather related. The two threat components include wind and water. Wind is likely to blow down trees, cover roads with branches and debris, and make many rural or semi-rural routes impassable.

Depending on one’s location, water accumulation is likely to be another issue with roadways making them impassable.

For either of these, vehicle ground clearance is important. The ability of the vehicle suspension to stay above debris and have the suspension travel to go over larger debris objects means a faster evacuation since one does not have to stop to deal with smaller obstacles.

There are full books written on good suspension systems as well as off-road capability, and very knowledgeable clubs devoted to doing so. Partake in these clubs! The vehicle does not have to be pushed hard or beaten to death, and modern trucks and off-road-intent SUVs can handle some significant terrain challenges. Understand your vehicle’s capabilities.

Water accumulation is especially hazardous since it can hide significant terrain features, such as a washed out road, sink hole, or sharp objects that will destroy tires. Furthermore, water entering the air intake system of the vehicle can hydrolock the engine. At best it is a time consuming fix, and at worst it can result in the engine’s destruction.

If one’s threat matrix has a high risk of flooding, a vehicle with a reasonable lift kit and a well-equipped snorkel system is a valid investment. The snorkel reroutes the vehicle air intake system through a snorkel that is usually 2-3 feet higher than stock. Well equipped snorkel systems also include routing axle breathers and in some cases exhaust pipes to a higher point on the vehicle.

One of the biggest factors in terrain capability is 4 wheel drive. In reality, 4WD is actually one rear wheel and one front wheel providing propulsion. With some modern trucks, electronic locking is available to ensure both rear and/or front wheels spin. 4WD is one of the most important factors that should be considered in a BOV.

Access for tools

If road debris is very likely (and it is), then getting at the tools to clear the path becomes important. Having a chainsaw, gas, a couple shovels, and some utility straps or chains readily accessible will make an evac go more quickly. Pick up trucks with a bed divider can help ensure the stuff you need right away is conveniently accessible at the rear of the bed, while the not-as-important-for-an-evac stuff stays securely in place near the front of the bed.

This type of accessibility can be more difficult in other vehicles, such as a sedan or enclosed SUV. In these cases, plan on either using the trunk or a vacant rear seat, or in the case of an SUV a rear cargo area divider, if available, for tool access . The tools WILL get dirty and muddy and need to be put back in the vehicle interior. Try to keep in mind this is an emergency evacuation scenario and something that will clean up isn’t an immediate concern.

Your spare tire and changing equipment should be equally accessible. If you must remove multiple containers from the vehicle to get at the spare, it is time wasted that may be crucial in an evacuation.

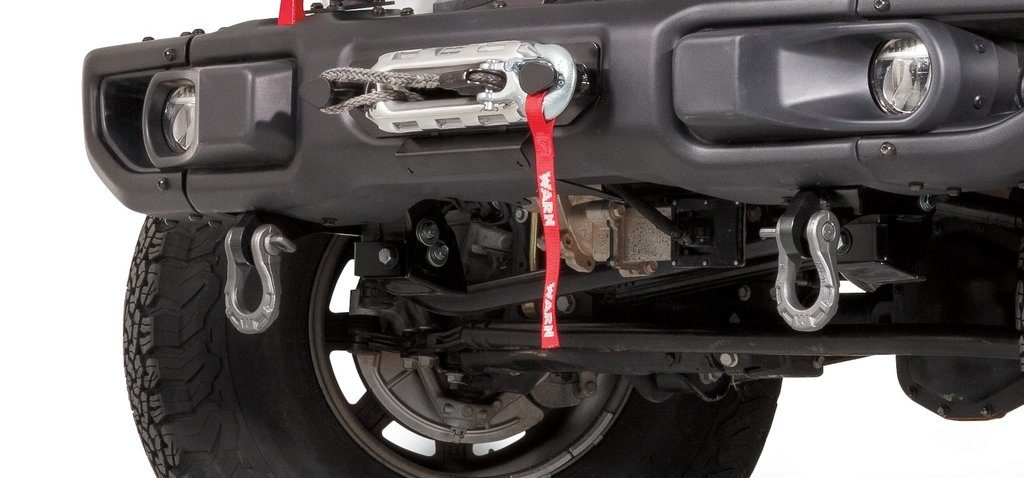

Recovery

A BOV intent vehicle should have recovery points. These are the hooks you see on Jeep bumpers or the D-shackles on some aftermarket offroad bumpers. All vehicles have tie-down points to facilitate shipping. Know where yours are and ensure they can be used as a recovery point if stuck. If you modify them, ensure they are rated for 3-4 times the vehicle weight.

A winch helps ensure the vehicle can self-recover if it becomes stuck. It consists of a high torque motor and spool which reels in a steel or synthetic (better) cable. Winching is an involved skill to do successfully and safely, and should be a part of your training. Again, get involved, even if only briefly, with an offroad club or take a class in this.

Vehicle reliability

We need it to go. Period. The vehicle must operate as intended when we ask it to. Most modern vehicles are quite reliable. While some have interesting quirks, they shouldn’t let you down. In the truck arena, Toyota is generally considered to reign supreme with the Tacoma and Tundra, though Ford and Chevy still make the list.

Along with reliability in design, regular maintenance is a must to ensure your BOV will perform as intended when you ask it to. We all tend to ‘get to that repair’ at some point, while eking out as much value from the vehicle as we can, but if you have a vehicle that will be intent as the family BOV, stay on top of its maintenance.

Ensure your vehicle has a full size spare. ‘Donuts’ (small spare tires designed to accommodate up to 50 miles or travel at low speeds) are utterly unreliable in an evacuation scenario.

Hauling capacity

Depending on the nature of an evacuation, you might be hauling a lot of stuff, or your go-bags only. A well-prepared go-bag is essential, but if you can save even more stuff from damage, you’ll do it. A BOV with hauling capacity facilitates this.

The first factor in hauling capacity is the weight/volume in the vehicle and its bed (if applicable). A Chevy Silverado Crew Cab bed has 72 cubic feet of cargo space and can bear nearly 2000 pounds of weight. A Toyota Tacoma bed approaches 37 cubic feet in volume and an bear 1175 pounds. For a hasty evac, either of these are sufficient to haul the ‘what you can grab’ items. For an evac with significant forewarning, more items might be removable.

For that, the tow rating of a BOV can be important. A trailer for extra gear, or better yet a camper or enclosed trailer with some living accommodation helps ensure you will have lodging, even if hotels are full. Most half-ton trucks (the compact trucks such as the Colorado, Ranger, and Tacoma) can tow approximately 7000 pounds maximum. Full size pickups can tow a typical 9500 pounds or so. These are maximums and if terrain and debris are a factor, the truck/trailer combination may not be capable of traversing the exit route.

For a decent blend of transporting volume and having livable space, the hobby of “overlanding” (motorized exploration travel, think backpacking from your vehicle) has produced many trailers that double as equipment storage, a galley, and a sleeping area via roof top tent. These types of trailers might be an excellent blend of utility and bug-out capability. (It’s also a growing and rewarding hobby…)

Mileage and range

Before the late 2010’s, we’d have to agree that vehicle mileage was the sacrificial lamb in these considerations. All of the characteristics that make a good bug out vehicle are typically not so good on gas mileage. But with manufacturers upping their fuel economy games, this is not as true as before. The Chevy Colorado with diesel engine can get 28 mpg. The full size Ford F-150 can get similar highway efficiency.

New non-diesel trucks are still capable of 22 mpg combined, which is a reasonable bump from just 2 decades ago.

Mileage and fuel capacity culminate in ‘range’, the total distance a vehicle can go without refueling. Some smaller vehicles sacrifice fuel capacity for mileage. Trucks typically do not. For a new vehicle shopper with BOV-intent, some vehicles offer multiple size fuel tanks. Get the larger one.

A Chevy Suburban only gets 19 mpg combined, but with its 31 gallon fuel tank, gets a range of 589 miles. A Chevy Colorado with diesel tops out at 580 miles range. A Ford F-150 diesel has a combined mileage of 24 mpg. With the available 36 gallon fuel tank, this yields a staggering range of over 800 miles.

It is important to remember that an evac situation will most likely not yield this kind of mileage. Getting 1/2 the anticipated mileage is close to worst case.

Mechanical vs Electronics

There is a LOT of talk about BOVs being as mechanical as you can get them. Carburators, manual transmissions, virtually no electronics… There are a lot of old school survivalists that swear by old vehicles that are still on the road. The notion is that mechanics are more reliable than electronics.

A lot of this can be confusion over causality, though. Newer vehicles with thinner metals increase efficiency, but make them less tolerant to rusting. Massive heavy engines made from recycled anvils are phenomenal for longevity, but don’t really help efficiency. Crush zones on vehicles that make occupants far safer means vehicles will be declared totaled with a lower threshold of damage than their Ford Flintstone counterparts. There’s a lot of reason there seems to be more older cars on the road than old ‘newer’ cars.

Electronics does not automatically equate to unreliability. Due to electronics vehicles have more power than ever using less fuel than ever to achieve it. Yes, electrical issues can be harder to pin down, but the free market is providing with things like OBD2 bluetooth devices that let you read trouble codes from an app. The shadetree mechanic is evolving with vehicle technology.

Muh Eee Emmm Peees!

An electromagnetic pulse (EMP) is a phenomenon resultant from a nuclear blast or possibly an intense and targeted coronal mass ejection (stuff from the sun jettisons away from the sun and hits Earth). Preparedness enthusiasts tend to keep this idea in the back of their mind, as even a rudimentary nuclear device can produce a substantial EMP. If such a device is detonated far overhead, the coverage area of a single EMP can be significant. EMPs are measured in volts per meter of open space, meaning that two points, 1 meter away, could have a voltage drop of 20 kilo-volts or more. Considering most solid state electronics are rated for not more than 50 volts, the idea that all electronics will be fried is a common one.

Many BOV builders prefer all-mechanical systems just for this eventuality. Many store extra electrical parts (such as spark plugs, condensers, computer modules, and more) in a Faraday cage (an enclosure meant to attenuate an EMP charge).

The reality of an EMP is that they do exist, though the risk is extremely low. The Carrington Event of the late 1800’s disrupted telegraph communications. It is important to remember that telegraph lines in those days were unshielded, and there was no real idea that such a phenomenon existed. Modern vehicles have decent hardening and shielding in place, and the vehicle itself is not a long antenna (meaning, it doesn’t have a large area in which to absorb EMP energy). Fantasy preppers believe most vehicles will fry. Engineers who test for electromagnetic compatibility (EMC) immunity aren’t so sure that the vehicle body and internal circuit hardening (usually properly placed ceramic capacitors) won’t provide sufficient shielding to allow the vehicle to run after an EMP strike.

If EMP is on your “I’m concerned” list, storing extra parts for your vehicle in a proper Faraday cage will be important. (Dismiss anyone telling you that a microwave oven or a shipping container are suitable Faraday cages. They are not.) Discussing your concerns with a qualified mechanic who can identify absolutely critical systems to making your vehicle run will be worth it.

And back to reality

The reality is that 90% of all threat events will be shelter at home. For the remainder, when the home is not an option, we need to have a safe, effective, and capable vehicle to get us away from the threat and to safety, however far that may be. While everyone’s needs may vary, it is hard to argue against a mid or full sized pick up truck with 4×4 as a suitable BOV. The platform offers extensive modification capability (there are custom mods out there for virtually any application) to ensure your vehicle is appropriate to your needs. With significant payload and towing capability, a fair amount of personal property can be saved. Depending on the nature of the threat, modern vehicle travel ranges can put your family well outside the area of effect on a single tank of fuel.