Every self defense instructor, every gun course, and every firearms expert will tell you, in every class, that situational awareness is the single best thing one can do to improve their odds of protecting themselves and their circle. The Cooper Codes of awareness are in almost every CPL class, and the “scan and assess” movement is encouraged after every drill practiced. This isn’t wrong, but is it as “right” as it could be? Is “awareness” truly being practiced?

In “Toward a Theory of Situation Awareness in Dynamic Systems” by Mica R. Endsley (Chief Scientist of the United States Air Force), situational awareness was originally defined as “the perception of environmental elements and events with respect to time or space, the comprehension of their meaning, and the projection of their future status.” This is very different than the lip service of “observe your surroundings”. Let’s break down the meaning in more detail, and see how it applies to protective training.

The perception of environmental elements and events

In most training classes, this is about as far as I see instructors present the concept. And sadly, even if students have been taught otherwise, about as far as they practice. This covers the observation portion of the scan and assess movement. The optical, tactile, audible, and olfactory inputs. The trainee is, if they do this part at all, allowing the observations to take place.

Yes, there is a lot we can do to train observation. When we are confronted with a threat, our brains focus on the threat itself, and our “brain processing cycles” are more dedicated to processing the information from what is in front of us. This sometimes manifests as sensory time dilation (we see things happening in slow motion) as well as tunnel vision (our brain quits processing peripheral vision information from our eyes). In fact, scanning and assessing is a way to force our brains to start processing our peripheral vision inputs.

There is far more needed than mere observation, though, to have true awareness around a scenario and therefore what is needed to be done in that scenario.

The comprehension of their meaning

This is the part of situational awareness that most practice of scanning and assessing or mere observation fails to include. The comprehension of the meaning of what is seen is a crucial aspect of awareness, if awareness is to go beyond anything but a visual deterrent (a bad guy sees you looking around and decides to wait for another target).

Observing the guy standing at the front of the gas station is a start, but when you observe he is looking up and down the aisles at cars and pumps and focusing on others who aren’t paying attention, or looking at people going into the convenience store then at their cars, the comprehension of meaning starts to show that he is casing the place and the patrons. At the other end of the possibility spectrum, he is completely engrossed in his phone’s screen, not looking up at all, and after enough observation isn’t even glancing up occasionally. Possibly, he looks over at the same vehicle multiple times, then at the street. Possibly there’s something wrong with his car and he’s expecting someone soon that will come and help.

These are all possibilities that can be derived when the observer begins to comprehend the meaning of what they are seeing.

The comprehension of meaning must also shed normalcy bias. When we are situationally aware, we are making a plan for when bad things happen. If we are at the grocery store and observe the back room of the store with an “Employees Only” sign, we can easily conclude that we aren’t supposed to be back there. Likewise the kitchen at the back of a restaurant, for instance. When we comprehend the meaning of these observations, with a “when things go bad” lens in place, the comprehension becomes “There is a back room. I can see an emergency exit that will trip the fire alarm. I am not supposed to go back there, but if I need to escape this way, I can easily do so.”

This becomes a far more complete awareness because we’ve comprehended the meaning behind the elements of our surroundings.

The projection of their future status

The projection of future status is a probable (and improbable) likelihood of the meaning of what has been observed. In the example of the guy standing in front of the gas station convenience store, there were a couple scenarios depicted. A projected status for the guy casing the place would be that he starts going up to people pumping gas and shaking them down for money. Another possibility is that he’s watching for unattended cars to rifle through before their owner comes out. In an innocuous example of him looking at a car with concern and the road, a possible projection of the status is that he is having car trouble and waiting for a friend, but there are other possibilities in mind as well.

The projection of future status must be performed with a risk (severity and likelihood) mentality in mind. It’s not always likely bad things are afoot, but our true situational awareness projects that these likelihoods are not zero-chance.

Conclusion

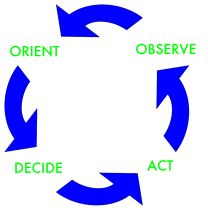

United States Air Force Colonel John Boyd developed the OODA Loop. Observe-Orient-Decide-Act. And in reality, every stimulus we experience in life causes us to go through an OODA loop. When bad things happen, we need to get through that loop fast and act to protect ourselves and our circle.

When we are truly aware, we are “observing”, but we are going well beyond that. When we are truly aware, we are “pre-orienting” the information we have to potential bad things happening. If the bad things happen, we are well through the major portions of the OODA loop, so we can very easily decide and act. Those decisions and actions will be informed by good observation, proper and complete (no normalcy bias!) orientation, and applicable decision and action based on extrapolating the meaning of the events.

When we train, don’t just go through the scan/assess motions. When out in the world, don’t just “see”. Comprehend meanings. Really understand the aspects of the things around you. Extrapolate observations into likely and unlikely projections.